Turning immune cells into therapy

Imagine using cells from your own body as a customised therapy against disease. What once sounded like science fiction is now reality with chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T cells). This innovative technology has transformed tumour treatment, particularly in B-cell malignancies, and is being explored for infectious diseases and chronic inflammatory conditions such as HIV/AIDS and lupus¹.

With their enormous therapeutic potential, CAR-T cells have become one of the most dynamic areas of biomedical research. This article outlines the fundamentals and latest developments, showing how CAR-T cells are reshaping immunotherapy. Together with our partner BPS Bioscience, we provide the latest research tools to support your CAR-T projects.

T cells – guardians of the immune system

Almost every nucleated cell in the body presents peptides (antigens) via the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). These antigens reflect the proteins currently being synthesised. If a cell is infected or genetically altered, foreign or mutated peptides are displayed on its surface.

Patrolling T cells use their T cell receptors (TCRs) to scan these antigens. Once a threat is recognised, T cells initiate an immune response, recruiting cytotoxic T cells and other effector cells to eliminate the abnormal cells. This makes T cells highly precise detectors of both pathogens and malignant transformations².

How CAR-T cells are designed

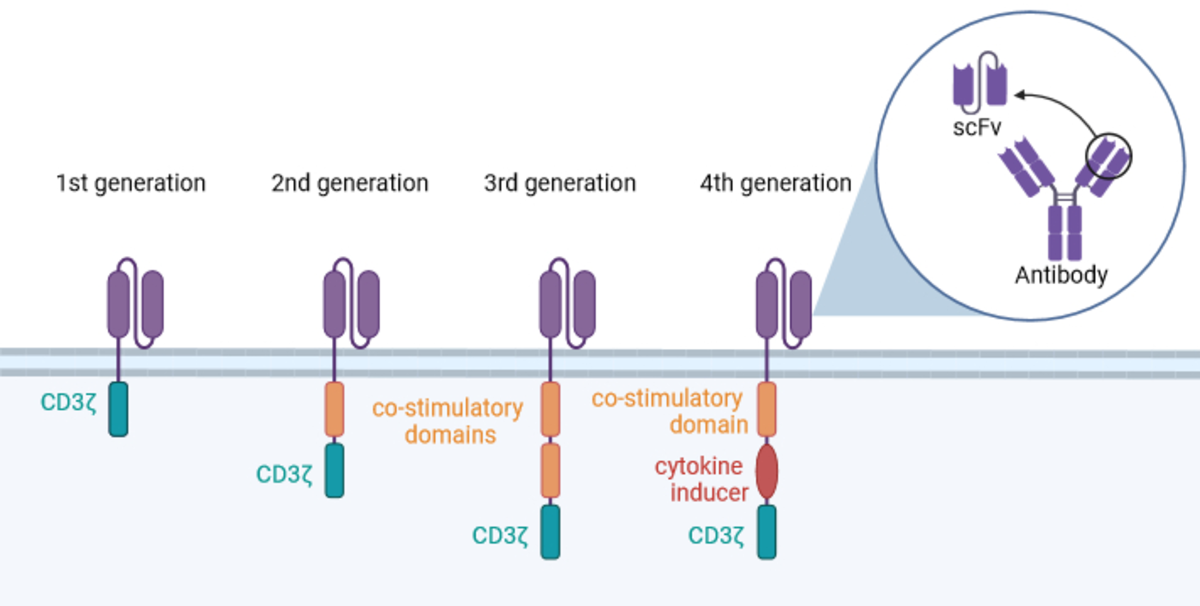

To harness this natural precision, conventional T cells are genetically modified to express chimeric antigen receptors (CARs). These synthetic fusion proteins are anchored in the cell membrane (Fig. 1).

Extracellular domain: a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from an antibody, linked by a flexible connector between heavy and light chains. This domain recognises target antigens.

Intracellular domain: includes the CD3ζ signalling unit and one or more co-stimulatory elements that activate the cell after antigen binding.

Scientific progress has led to four generations of CARs, each with distinct intracellular domains (Fig. 1):

First generation: CD3ζ alone – insufficient for effective tumour therapy³.

Second generation: CD3ζ plus one co-stimulatory molecule.

Third generation: CD3ζ plus two co-stimulatory domains.

Next generation: CD3ζ plus a cytokine production domain and one co-stimulatory domain, enabling modulation of immune responses⁴.

These improvements have enhanced the persistence and efficacy of CAR-T cells⁵.

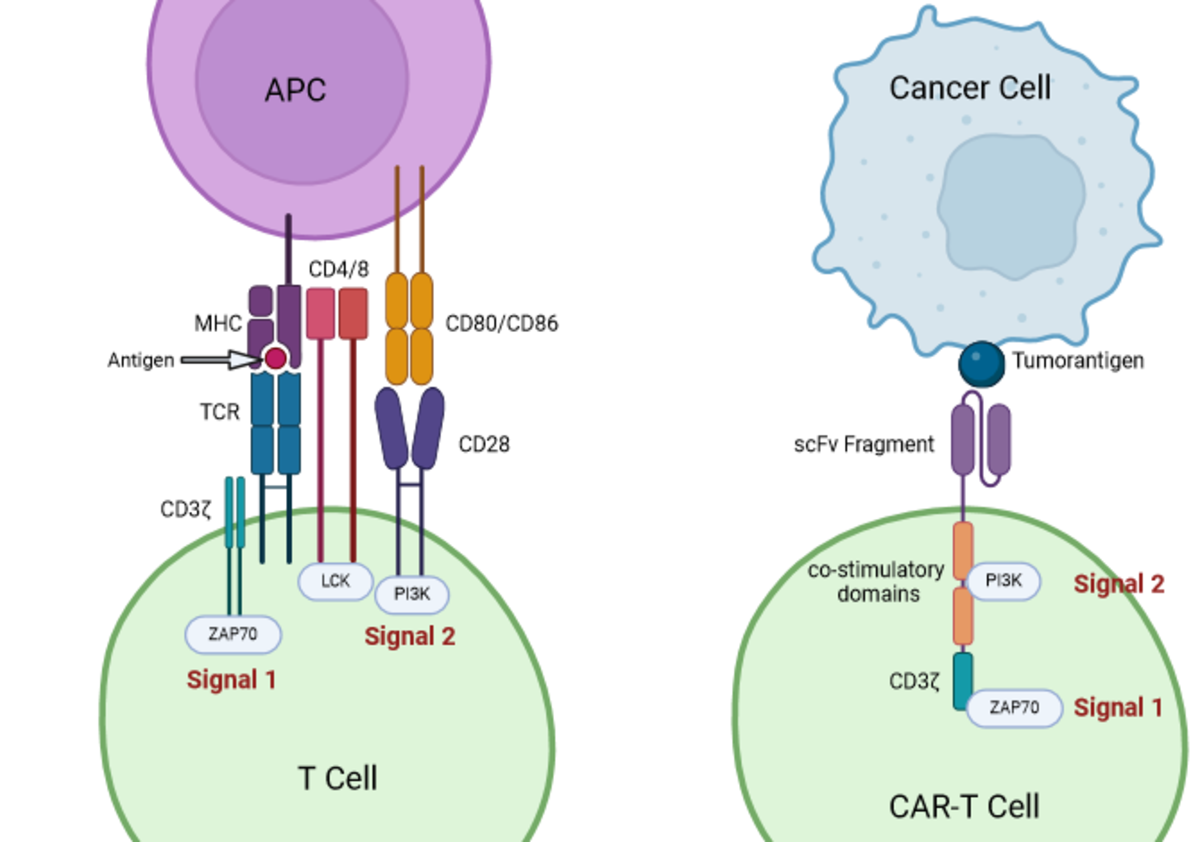

Comparing T cell and CAR-T signalling

In a normal immune response, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) display MHC–antigen complexes to T cells (Fig. 2). T cell activation requires two signals:

Signal 1: binding of the TCR/CD3ζ complex to the MHC–antigen complex.

Signal 2: a co-stimulatory interaction (e.g. CD28 binding to CD80/CD86) that triggers downstream signalling cascades.

CAR-T cells bypass the need for MHC presentation. Their extracellular scFv recognises antigens directly on tumour cells. The CD3ζ domain provides signal 1, while the co-stimulatory modules provide signal 2. The absence of co-stimulation explains the failure of first-generation CARs³.

Because many tumour cells evade immunity by downregulating MHC molecules, CAR-T cells’ independence from MHC is a major advantage⁶.

Therapeutic application and the role of CRISPR/Cas9

CAR-T cell therapy involves isolating T cells from the patient, engineering them to express CARs, and expanding them in culture before reinfusion. Once inside the patient, CAR-T cells target and destroy cells carrying the relevant antigen⁷.

This approach has revolutionised cancer treatment, but challenges remain, including limited persistence and functional exhaustion of CAR-T cells. Integrating the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system offers new solutions⁸.

CRISPR/Cas9 – boosting CAR-T efficacy

CRISPR/Cas9 is derived from the bacterial immune system, which uses small RNA guides and the Cas9 nuclease to destroy invading DNA. In research, CRISPR/Cas9 enables precise genetic edits to improve CAR-T therapies.

T cell exhaustion: tumour microenvironments often suppress effector functions, leading to poor CAR-T expansion. Editing checkpoint receptors and transcription factors with CRISPR can restore T cell function⁹.

Enhanced antigen binding: targeted modifications improve CAR affinity for antigens.

Despite these advantages, off-target effects remain a risk. Optimising sgRNA design and selecting alternative Cas nucleases are essential to reduce unintended mutations⁸.

Research support from BPS Bioscience

BPS Bioscience provides a broad portfolio of products for CAR-T and CRISPR/Cas9 research.

Lentiviruses for CAR gene transfer with antigen-specific constructs tailored for B-cell tumours.

TCR CRISPR/Cas9 lentiviruses for targeted TCR editing.

Knockout and reporter cell lines to study immune cell function and signalling pathways (e.g. NFAT cytokine production).

Untransduced T cells as negative controls in CAR-T assays.

Product highlights

| Cat-No. | Item | Size | Price (CHF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 78556 | TCR Knockout NFAT-Luciferase Reporter Jurkat Cell Line | 2 vials | price on request |

| 78539 | TCR Knockout Jurkat Cell Line | 2 vials | price on request |

| 78363 | B2M Knockout NFAT Luciferase Reporter Jurkat Cell Line | 2 vials | price on request |

| 78391 | B2M/CIITA Double Knockout THP-1 Cell Line | 2 vials | price on request |

| 78552 | TCR/B2M Knockout Jurkat Cell Line | 2 vials | price on request |

| 78390 | CIITA Knockout THP-1 Cell Line | 2 vials | price on request |

| 78389 | B2M Knockout THP-1 Cell Line | 2 vials | price on request |

| 78062 | TCR CRISPR/Cas9 Lentivirus (Non-Integrating) | 2 x 500 ul | 1'230.00 |

| 78600 | Anti CD19 CAR Lentivirus (CD19 ScFv-CD8-4-1BB-CD3z) | 50 ul | 1'607.00 |

| 78757 | CD8+ TCR Knockout NFAT-Luciferase Reporter Jurkat Cell Line | 2 vials | price on request |

| 78775 | Anti CD19 CAR Lentivirus (CD19 ScFv-CD8-4-1BB-CD3z, eGFP) | 50 ul | 1'672.00 |

| 78655 | Anti BCMA CAR Lentivirus (Clone C11D5.3 ScFv-CD8-4-1BB-CD3z) | 50 ul | 1'389.00 |

| 78171-1 | Anti CD19 CAR-T Cells | 1 vial | 1'878.00 |

Innovative power in immunotherapy

CAR-T therapy is one of the most promising advances in oncology and is already expanding beyond cancer to other diseases. By combining CAR-T cell technology with CRISPR/Cas9 editing, researchers aim to overcome current barriers and unlock new therapeutic opportunities.

With BPS Bioscience as a trusted partner, scientists have access to cutting-edge tools to drive CAR-T and CRISPR research forward, shaping the future of immunotherapy.

References

BPS Bioscience. CAR-T cell therapy technical note. Available at: https://www.bpsbioscience.com/car-t-cell-therapy-technical-note (accessed 07 February 2024).

Labanieh, L., Majzner, R. G. & Mackall, C. L. Programming CAR-T cells to kill cancer. Nat. Biomed. Eng.2, 377–391 (2018). doi:10.1038/s41551-018-0235-9

Mitra, A. et al. From bench to bedside: the history and progress of CAR-T cell therapy. Front. Immunol.14, 1188049 (2023). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1188049

Onmeda. Cytokine overview. Available at: https://www.onmeda.de/gesundheit/anatomie/zytokine-id201341/ (accessed 07 February 2024).

Tomasik, J., Jasiński, M. & Basak, G. W. Next generations of CAR-T cells – new therapeutic opportunities in haematology? Front. Immunol.13, 1034707 (2022). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.1034707

Srivastava, S. & Riddell, S. R. Engineering CAR-T cells: design concepts. Trends Immunol.36, 494–502 (2015). doi:10.1016/j.it.2015.06.004

BPS Bioscience. CAR-T cell tools for engineering the immune system. Product catalogue.

Wei, W., Chen, Z.-N. & Wang, K. CRISPR/Cas9: a powerful strategy to improve CAR-T cell persistence. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 12317 (2023). doi:10.3390/ijms241512317

Manriquez-Roman, C., Siegler, E. L. & Kenderian, S. S. CRISPR takes the front seat in CAR-T cell development. BioDrugs35, 113–124 (2021). doi:10.1007/s40259-021-00473-y

BPS Bioscience

Experts in protein design, expression, purification, and characterization, cell line and lentivirus engineering, and biochemical and cellular assay development.

Shop ONE-Step and TWO-Step Luciferase Assays by BPS Bioscience